INNOCENCE, a solo-show of Chicago-artist Jake Fagundo’s paintings and Sulk Chicago’s inaugural exhibition

“I can’t remember the last time I was in a room with this many cis men,” I joke to my friend Celia and their high-school friend, who I just met a few minutes ago and whose name I’ve already forgotten.

We’re sitting on a burnt-orange velvet loveseat, the only furniture in the spacious one room gallery. Under the impression this is a home gallery, I keep asking Celia where the rest of the owner’s furniture is, whether they think it’s stored away somewhere or if their interior design is really this minimal. We’re blatantly surveying the crowd and passing judgement as though we’re game show hosts. I’m particularly interested in a small huddle of young men who are all dressed in ill-fitting jeans and faded, oversized polos that are almost identical to the ones my own father wears. There’s a certain charm to their desire to embody the oblivious nonchalance of suburban Midwestern men, a rebuke of cosmopolitan fixations with expensive designer clothing. But, I’m digressing.

“There were way more women here earlier!” The friend whose name I can’t remember reassures me. I take a sip from the Tecate beer that I’ve been nursing and cast my gaze around the room.

Whenever I attend gallery openings, I’m often fascinated by the crowd because it feels like low-hanging fruit, an easy indicator of the social circles the artist occupies and who their work resonates with. INNOCENCE, a solo-show of Chicago-artist Jake Fagundo’s paintings and Sulk Chicago’s inaugural exhibition, is the first gallery opening that I’ve been to since 2019. I feel distinctly out of touch. Unlike most gallery openings I attend, there’s no one that I recognize besides Celia and, later in the night, an Instagram mutual who I’ve never met in-person, so we just wave politely at one another. In lieu of catching up with old friends and ex-coworkers, I find myself forced to look at the paintings—something few people actually do on opening night.

Opposite the loveseat where Celia and I have deposited ourselves for the night is Fagundo’s large, horizontal oil painting Hope it don’t rain all day (2021), which features Fagundo as a child, standing in front of a tranquil body of water. He’s holding a fishing rod in his right hand and a bucket in his left hand and is wearing a bulky, orange rain jacket that appears to faintly reflect the murky green of the grass. His face is somber, rendered in a lifeless gray color. I lean closer to inspect the painting and can’t help but feel there’s a certain forlorn quality to this scene, especially the shadowed, indistinct face. The image is obviously not a celebratory snapshot taken by one of his parents after Fagundo snared a fish. The sparseness and flatness of the composition make me feel disappointed for the child. His excitement was squashed by the rain, as alluded to in the title of the work and the murky clouds overhead. He’s been robbed of a day that promised to be filled with fun, the alluring possibility of catching an elusive fish.

When I first saw the painting, I immediately turned to Celia and said, “Wow, this reminds me of my childhood.” They nodded in agreement. There’s an almost identical photo on my mother’s desk of me at the age of six, standing beside a stagnant, algal-green pond near my grandparents’ trailer in Michigan. I’m clutching a long, mesh net and a purple plastic bucket with an arched, yellow handle. I was catching frogs, one of my favorite summertime activities as a child. Unlike Fagundo, I am chubby and ecstatic in my photo, with a wide, beaming grin, which makes me more intrigued by Fagundo’s sobering paintings.

Since several of the paintings in the exhibition are direct recreations of childhood photos and home video stills, I’m left to wonder: Does Fagundo retroactively imbue these images with this forlorn texture, or does he really look that miserable in the original image? Has Fagundo superimposed his present emotional distress into these nostalgic memories? In an effort to understand where and how he might have lost his innocence; does he look to his childhood for signs of delinquency and criminality lurking in the shadows? Does he subconsciously want to find those qualities there?

As the title of the exhibition suggests, Fagundo is interested in innocence. The 11 paintings featured in the exhibition were made following Fagundo’s arrest by Chicago Police in 2020 and his subsequent legal battle. He faced a potential twenty-year prison sentence. I won’t detail the specifics of Fagundo’s legal troubles further, because I personally refuse to legitimize the carceral logic that permeates most of our society and encourages us to see people who’ve been arrested for or convicted of a crime as permanently marked: a criminal.

I was skeptical when my friend invited me to the opening and described the work to me, rightfully suspicious of most art made by white artists about the US carceral system. I half expected Fagundo to ignore his own experiences with the criminal justice system and make the faux pas of turning his gaze to Black and brown people, using their present and historic struggles against the police and incarceration as visual fodder. I was not expecting him to acknowledge the details of his own legal case, the experience of being arrested and, subsequently, being put on house arrest, or to grapple with how the threat of potentially going to prison for two decades loomed over him and affected his mindset. In short, I presumptuously thought the work was going to be fetishistic. I was wrong.

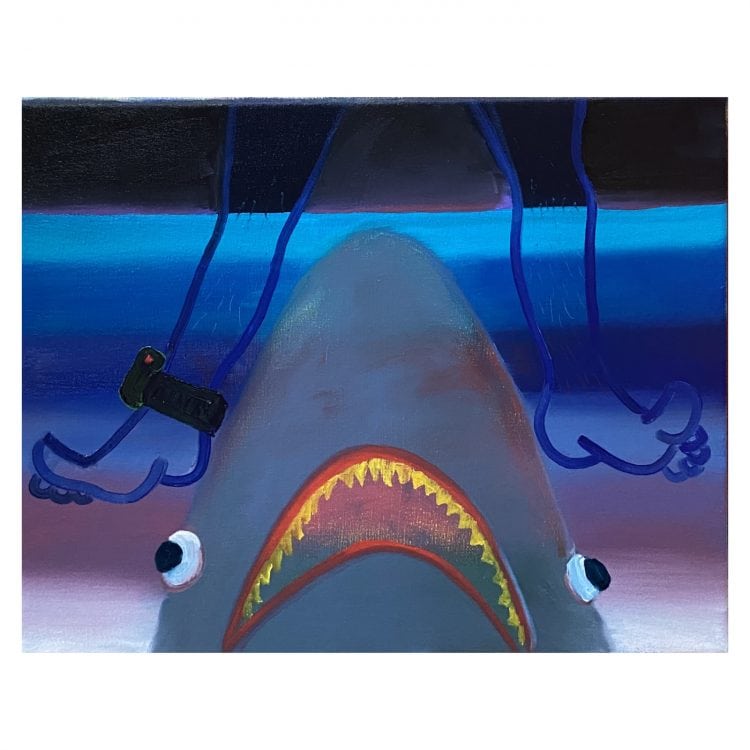

Jake Fagundo, “Ain’t no way in the world I’m goin’ out that front door,” 2021. Photo courtesy of the artist.

One of my favorite paintings featured in INNOCENCE is Ain’t no way in the world I’m goin’ out that front door (2021). It’s devilishly funny, referencing the visual iconography of Roger Kastel’s infamous poster for the 1975 blockbuster Jaws, except Fagundo’s shark is somewhat less menacing with ogling eyes that point in different directions. A pair of legs, streaked with scraggly, blue hairs, straddle the shark. They are presumably Fagundo’s own since there’s an ankle monitoring bracelet clasped around the right ankle. The background is an indistinct gradient of blues and purples, suggesting that Fagundo might be wading ankle-deep in the water. Both the shark and the ankle-monitor are distinct threats, one potentially devouring Fagundo and the other alerting the Sheriff's Monitoring Center if he leaves his residence. Despite being able to avoid a lengthy stay in the Cook County Department of Corrections, Fagundo experiences a sense of foreboding—captured in this ominous painting—that there is something monstrous just underneath the surface, waiting to gobble him up either way.

I’m a particular fan of Fagundo’s smaller paintings near the entrance of the gallery, Always be a good boy and never play with guns (2020) and Welcome to the terrordome (2020). They are recreations of a $40 check issued to Fagundo by the Inmate Trust Fund and a badge which declares him a guest of John Cooke respectively. Presented directly opposite one of the large-scale paintings of Fagundo as a child, dressed as Dracula, the paintings are painfully mundane and sobering. The central struggle in Fagundo’s paintings seems to be this question of how someone can represent the experience of being arrested and charged with a crime, explaining the malaise, the daily dread of not knowing whether you’ll spend two decades in federal prison while life continues around you.

How do you explain being processed at the police precinct: sitting on a squat, circular stool while your wrist is handcuffed to a post on the wall that’s just far enough away that you can never sit comfortably? Meanwhile, police officers mull back and forth, making crude comments about the inmates and waiting for the State’s Attorney to decide what charges they will prosecute you for. Eventually, the detectives deign to enter the interrogation cell, explain your charges and ask if they can ask you some questions, which you (wisely) refuse to without counsel present. How do you explain what it feels like to be shepherded into the back of a police paddy wagon with at least 30 other men, most of them Black and brown men? All of you are handcuffed. There are no seatbelts, and the driver mercilessly drives well above the speed limit, hitting every pothole he can on the highway, and you desperately clutch the steel bench, apologizing whenever you bump into the men on either side of you.

How do you account for the time spent being transferred from holding cell to holding cell in the jail’s subterranean labyrinth? There are no clocks anywhere, which disorients you as intended. You only have a vague sense of time because the other inmates keep talking. And shitting. There is one stall in the corner of the cell. There is no toilet paper or soap. The room starts to smell like a warm heap of rotting, maggot-filled meat. Everyone asks each other what they’re in for, mostly drug charges. They try to decide whether they’ll be able to get out on bail, recounting their previous arrests or anecdotes from brothers, uncles, cousins, friends, friends of friends. Maybe, if you’re lucky, the guards serve you some food. A sandwich. It’s just two slices of dry bologna on stiff white bread. And a pre-packaged juice, which you trade for another sandwich.

Finally, you’re brought to a holding cell upstairs. You can see daylight through the window. By the time they call you before the judge, it’s dark outside. You stand in front of the judge, blinking slowly. He sets the terms of your bail, and you nod. It’s an unthinkable sum of money. How will you pay for it? You have no idea. And then you’re brought back to one of the subterranean holding cells from earlier. It hasn’t been cleaned and the shit smell makes you lightheaded and faint. You’re released. You stand outside the jail without any of your belongings, which are back at the police precinct where you were originally booked, several miles from where you are now.

How do you explain any of that to your family and friends without experiencing the disembodiment, the dehumanization, all over again?

I would argue, you can’t. The criminal justice system is designed to forcibly strip people of their humanity, leaving you with enduring memories of being human cattle. It is a deeply shameful experience. It’s impossible to describe the mental anguish, and Fagundo seems to recognize that implicitly. He deftly avoids politically charged images of the courtroom, jail, or the explicit actions that led to his imprisonment. Instead, he acknowledges his legal predicament through ephemera: the check, the badge, the court case name “United States of America v. Jacob Michael Fagundo,” which hovers above an inferno, and his signature above a line naming him as “defendant.” There’s a subtlety to this choice that’s profoundly effective. These works draw our attention to bureaucratic pieces of paper that, when presented alongside images from Fagundo’s childhood, make us wonder:

How does the playful child become the person indicted by these pieces of paper, an inmate, a defendant, an enemy of the state?

And, in a body of work that demonstrates a profound maturity, Fagundo is attempting to answer that question.

Note

INNOCENCE is on view through October 31 by appointment only. More information can be found HERE.

日本語

日本語 English

English